Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

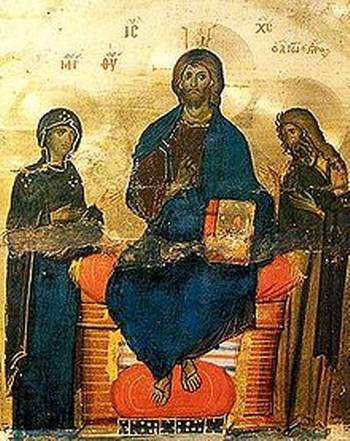

AZ23. Triptych with Deesis and Saints

Mount Athos, late 16th or early 17th century

Panel (extended): 24.8 x 37.5 cm![hideselects= [On] header =[Convert size] body = [Click here to show the size in inches] Click here to convert metric size to imperial](images/inches.gif)

Condition: Conserved by Laurence Morrocco.

Provenance: Art market Germany

Inscriptions: Greek inscriptions identify the saints and other figures on the triptych.

No. 23. Detail

No. 23. Detail

No. 23. Detail. Left wing with St Athanasius and the Assembly of the Archangels

No. 23. Detail. Right wing with Sts Cosmas and Damian and St Basil

The centre panel of No. 23 shows the Deesis: Christ seated on a red cushion on a backless wooden throne, a smaller red cushion beneath his feet. He wears the traditional garments of Greek antiquity: a blue himation over the left shoulder and exposing the right side of the body where we see a red chiton with a golden clavus on the shoulder; his right hand is raised in blessing as he looks towards the spectator while the left hand holds the gospel open at the words 'Μάθετε απ' εμού ότι πράος ειμί και ταπεινός τη [καρδία]':‘Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in [heart]' [Matthew 11:29], an unusual text not commonly found in Pantocrator icons1. On either side, standing behind the throne is the Mother of God, in a red maphorion and St John the Baptist attired as a desert ascetic with a brown cloak.

The choice of images depicted on the wings suggests a monastic origin for our icon. In the upper zone on the left we see St Athanasius of Alexandria2 and on the right St Basil the Great, both bishops, ‘doctors of the church’ and considered founders of monasticism in the fourth century. In the lower zones we see the Synaxis of the Archangels, a theme concerned with immateriality and the angelic hierarchy3, and Sts Cosmas and Damian, third century martyrs and miraculous healers. The triptych is thus a compendium of spiritual exhortation, calling its owner, or whoever contemplates it, to spiritual endeavour through the intercession, or the witness, of Christ, the Mother of God and various saints and their feasts.

The Greek word ‘Deesis’ means prayer or ‘entreaty’ and is usually rendered in English as Intercession. From the thirteenth century onwards that was the meaning of the image of Christ Enthroned attended by The Virgin and John the Baptist interceding on behalf of humanity at the Throne of Judgment. The theme is well known through the famous mosaic in Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Fig. 1). The composition later grew into the so-called Extended Deesis or Great Deesis where many further intercessors were added. The main row of fifteenth century iconostases in Russian churches included altogether fourteen saints ranked either side of Christ, facing inwards towards him. However, the present icon seems to follow an older tradition, examples of which are known from the 9th century, where the meaning was not so much that of intercession but rather that of honouring Mary and John as the first witnesses of Christ’s divinity4.

Fig. 1. Deesis. Mosaic, 13th century, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

Fig. 2. Deesis, St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai. 12th century

Our Deesis, especially in its strong red, blue and gold colouring, relates to an icon in St Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai that dates from the twelfth century (Fig. 2). There is one noticeable difference: in our icon the hands of the Mother of God are folded across her chest with the palms inwards. St John has a similar gesture with one hand opening towards Christ. Such postures expressing self-containment are an unusual departure from the majority of Deesis icons where both gestures and looks are directed towards the Saviour. I have found one other example located, not surprisingly, on Mount Athos (Fig. 3.)

Fig. 3. https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/photo/greece-chalkidiki-mount-athos-peninsula-world-royalty-free-image/521272652

Also unusual is the regard of both John and the Virgin. This is not focused on Christ, as one usually sees, but, like Christ, they look directly towards the spectator as though inviting his or her participation. These differences suggest that our icon is associated with monastic life and the intensive practice of interior prayer known as Hesychasm.

Hesychasm, (from the Geek hesychia meaning stillness and silence), is the following of Christ’s injunction: ‘When thou prayest, enter into thine inner chamber, and having shut thy door, pray to thy Father who is in secret’ (Matt. 6:6) together with Paul the Apostle’s ‘Pray without ceasing’ (Thessalonians 5:17). Hesychasm is a way of life at the heart of Orthodox monasteries since their origins in fourth century and employs meditation techniques similar to those found in Buddhism, Hinduism and the Sufi tradition of Islam that include special physical postures and exercises, consciousness of breath, mantric repetition (the ‘Jesus prayer’) and the cultivation of inner silence and freedom from the turmoil of thoughts and emotions. St Gregory Palamas was one link in a long chain of teachers who revived and enhanced Hesychasm in the fourteenth century. But the tradition is much older. We find it in the writings of the Desert Fathers of the third century though, as the Oriental parallels imply, it is a universal tradition as old as of human consciousness5. The Hesychasm of Palamas influenced the art of fourteenth century Byzantium and Russia and its echoes continue to be found for two hundred years or more providing, it can be said, a key to a deeper understanding of certain icons. A further revival was to take place through Feofan the Recluse in Russia in the nineteenth century6.

The construction of our triptych is almost identical to one in the British Museum (See Fig. 4). The double-stepped arch that receives the wings when folded is the same and we find the same arrangement on the wings with bust-length saints in the upper parts and full-length standing figures below. The BM catalogue notes refer to ‘The depressed triple arch with the double moulding . . . found in a series of triptychs which are associated with Mt Athos. The closest to the British Museum example is one in the Museum of the City of Athens’7.

Fig. 4. Triptych with Dormition and Saints, 16th century. British Museum |

No. 23. |

No. 23 with wings closed.

Footnotes:-