Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

AZ15. Christ the True Vine

Circle of Angelos Akotantos, second quarter of the 15th century

Panel: 24 x 64 cm x 1.6 cm thickness![hideselects= [On] header =[Convert size] body = [Click here to show the size in inches] Click here to convert metric size to imperial](images/inches.gif)

Condition: Good condition. A condition report including initial technical analysis was carried out under the direction of Katherine Ara of Katherine Ara Ltd. [Click here] (www.katherineara.com), London

Provenance: Private collection California, USA. The Christies stencil marks on the back (see Fig. 6) refer to a private owner named Macpherson in London in 1914.

The Temple Gallery expresses its deepest gratitude to Professor Maria Vassilaki who kindly offered corrections and made valuable suggestions that have been incorporated into the text that follows.

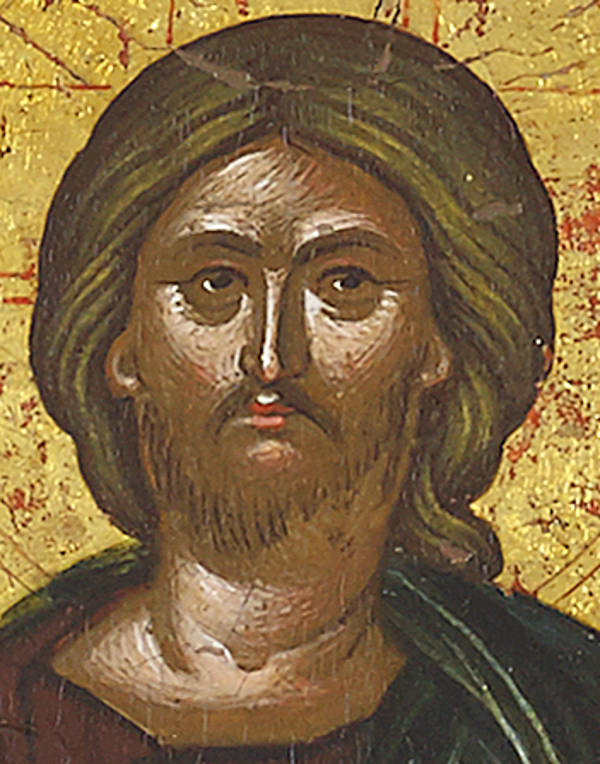

No. 15. detail

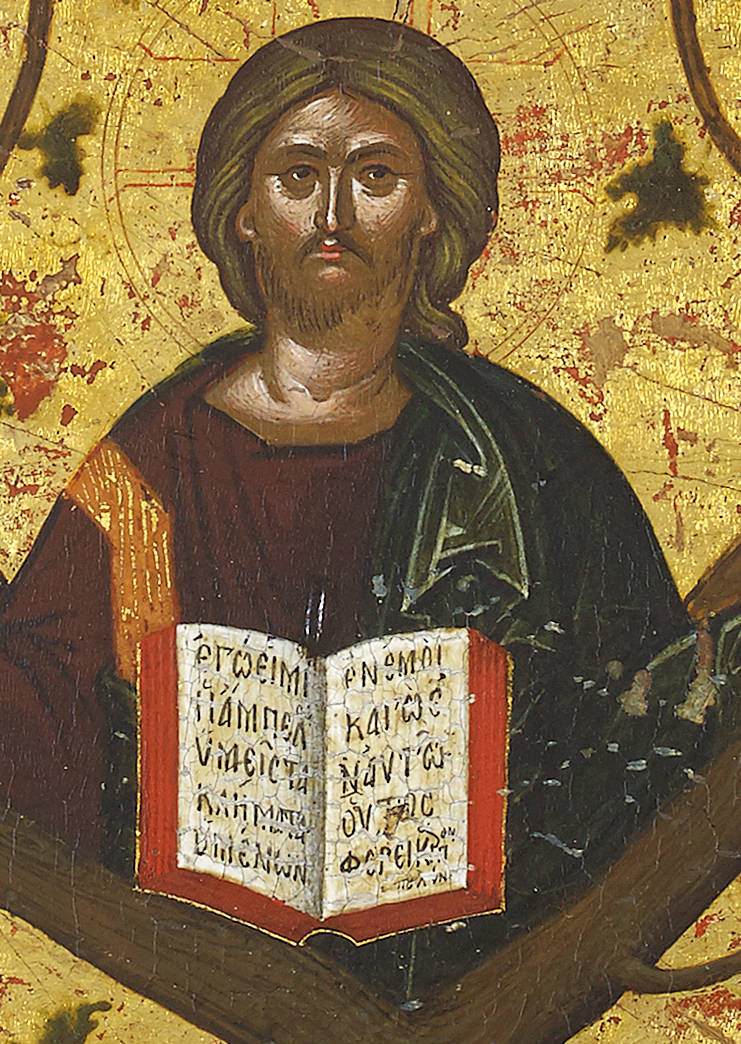

No. 15. detail

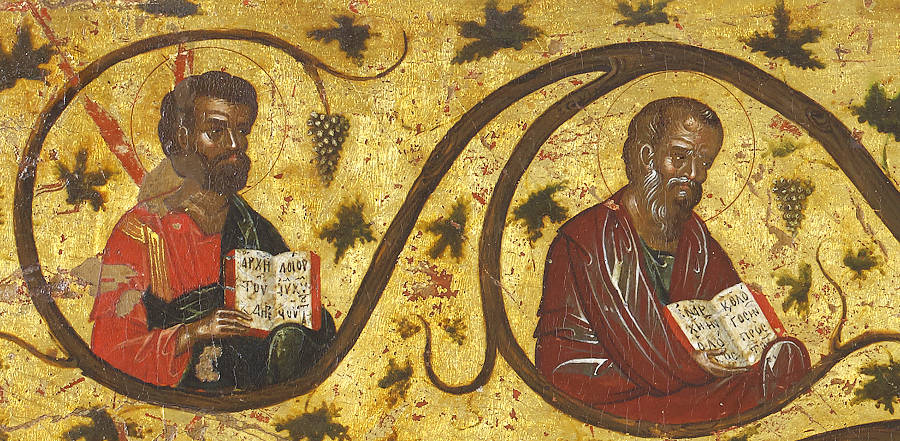

No. 15. detail St Mark (left) St John (right)

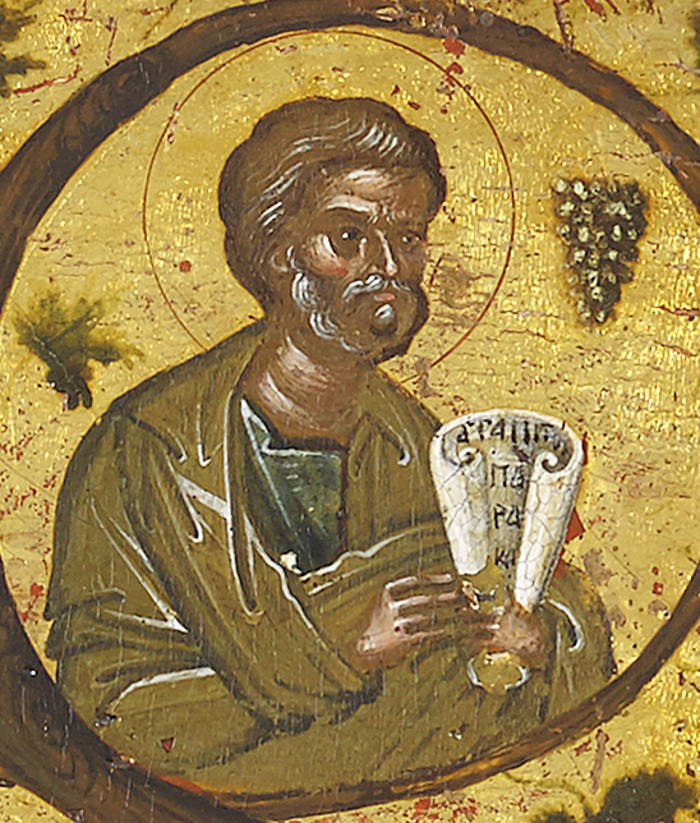

No. 15. Detail. St Peter

No. 15. Detail St Paul(left) St Matthew (right)

No. 15. detail. St Phillip (left) St Andrew (right)

No. 15. Detail. St Simon

No. 15. Detail. St Bartholomew(left) St Thomas (right)

In the centre of the icon is the bust of Christ, depicted as Pantocrator. His arms are raised in an open gesture and he blesses with both hands while gazing directly at the onlooker. Before him the Gospel book is open at the words of St John ‘ΕΓΩ ΕΙΜΙ Η ΑΜΠΕΛΟC YMEIC ΤΑ ΚΛΗΜΑΤΑ Ο ΜΕΝΩΝ ΕΝ ΕΜΟΙ ΚΑΓΩ ΕΝ ΑΥΤΩ ΟΥΤΟC ΦΕΡΕΙ ΚΑΡΠΟΝ ΠΟΛΥΝ ‘I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit,’ (John 15:5). Proportionally larger than the apostles, Christ is placed at the centre of the vine tree, which grows up from a low hill, and from which the branches extend laterally across the panel, their tendrils looped around busts of the twelve apostles who face inwards. The composition is symmetrical and the flow of the design is elegant and rhythmic. A pattern of vine leaves and bunches of grapes punctuate the space.

Fig. 1.

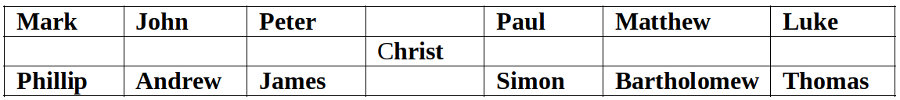

The apostles are arranged on either side of Christ in two rows of six (Fig. 1). A prominent position in the upper row, to the left of Christ is given to Peter, holding a half open scroll, and to Paul, to the right of Christ, holding an open Gospel book; both are fully enclosed within the circling branch whereas for the other apostles the tendril leaves a space without closing on itself. Beyond Peter and Paul are the four Evangelists each holding an open Gospel book and inscribed with a relevant text. In the next row are Phillip, Andrew, James, Simon, Bartholomew and Thomas all of whom are holding closed scrolls in their left hand while they gesture with their right hand or, if in contact with the scroll, are covered.

In the great majority of icons, the height exceeds the width so in this case the form is unusual and relates to its function in the church. As already pointed out, the horizontal shape of an icon indicates it was originally intended for a templon ‘above the entrance to the sacrificial altar’1 in other words above the Royal Doors of an iconostasis.

The icon illustrates the text from the Gospel of St John 15:1-5 (KJV):

1. I am the true vine, and my Father is the husbandman.

2. Every branch in me that beareth not fruit he taketh away: and every branch that beareth fruit, he purgeth it, that it may bring forth more fruit.

3. Now ye are clean through the word which I have spoken unto you.

4. Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself, except it abide in the vine; no more can ye, except ye abide in me.

5. I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit: for without me ye can do nothing.

Images of the vine as a symbol of abundance are common in the Roman world and in Early Christian churches in Jordan2 , Syria3 and elsewhere but a specific illustration of the verses John 15:1-6 does not exist in Early Christian art or in Byzantine imagery until its invention by Angelos Akotantos (active 1425-1450). There are visual analogies of Christ the Vine with the Tree of Jesse depicting the Mother of God with the Old Testament forefathers, which appears already in the 12th century as in the church of San Clemente in Rome. But the analogy is only visual; the theological significance of the Tree of Jesse points to the Incarnation and its implications for the redemption of humanity4. In the case of the icon No.15 the painter employs the image of the Vine as a symbol of the unity of the Church, which in the late 1430s was an all consuming political and theological issue. Since the Great Schism of 1054 the Churches of Rome and Constantinople had stood in opposition to each other and now their reunification was being debated at the Seventeenth Ecumenical Council or, as it is more commonly known, the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1438/39.5 In later images of Christ the Vine, i.e. when the theme was reintroduced in the middle of the sixteenth century after a long period when it was not used, the theological emphasis had again changed and the icon is no longer seen as a symbol of the Union of the Church but as a reference to the Eucharist6.

During the first half of the fifteenth century a number of Constantinopolitan master painters had relocated to Candia (today Iraklion) the capital of Crete. Shortly after the Latin conquest of Constantinople in 1204 the island of Crete became a Venetian possession and it is in Candia, sometimes referred to as the ‘New Constantinople’, that we find the final flowering of the Paleologan tradition of Byzantine art. The leading exponent of this movement and its greatest painter, the founder of the Cretan School, was Angelos Akotantos active from about 1425 until his death in 1450.7 The Orthodox Patriarch travelled from Constantinople to Italy for the Council of Ferrara with an entourage of seven hundred people one of whom (we can imagine) could have been Angelos, the leading painter of his day and a supporter of the Union of the Churches. There is no direct evidence of this but, as we know from his will, he did make a journey to Constantinople in 1436.

In the late 1430s the Union of the Churches was the burning issue of the day. The dispute between Rome and Constantinople extended to theological, ecclesiastical, political and military matters. Greeks themselves were divided on the issue but there is strong evidence to suggest that Angelos was pro-Unionist. Maria Vassilaki argues that his appointment by the Venetian authorities to the religious office of Protopsaltis (first chanter) of Candia, can be an indication of his favourable attitude toward the Latin Church. It is also significant that he painted at least ten icons of the embracing apostles Peter and Paul, symbolizing the Unity of Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy8. Another symbol of the church’s unity is the icon of Christ the True Vine. ‘The iconographic subject of the Vine indicates primarily the unity of the Church, especially since Christ, its institutor, is depicted surrounded by the Apostles’9. Three icons of the subject are signed by Angelos10 and it is possible and even likely, if we bear in mind that multiple icons of the same subject is characteristic of the painter, that he painted more: ‘Angelos was accustomed to repeating the same subject in a large number of his icons’11. Apart from the three signed icons already mentioned, one other icon of Christ the Vine of highest quality in the Cretan style of the second quarter of the fifteenth century is known (Fig. 2). This icon has been attributed to Andreas Ritzos, who is thought to be Angelos’ greatest pupil, but as far as I know that icon has not been studied by Greek scholars yet. It was sold at Sotheby’s in 199512 and was subsequently in the Temple Gallery in 201613. The present example, No. 15, is a new discovery. Thus, there are five icons of Christ the Vine datable to the second quarter of the fifteenth century. All other known examples are later by a century or more.

Fig. 2. Christ the Vine, private collection, Brussels.

Apostolos Mantas suggests that after the failure of the project to unite the churches there was no longer ‘ideological pressure’ and that the use of the image was abandoned. Its next iteration was a hundred years later in a fresco by Theophanes Strelitzas Bathas (‘Theophanes the Cretan’) in the refectory of the Great Lavra Monastery on Mount Athos from 153514. We see already in that work and in subsequent works in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, how the evolution of the Cretan style develops away from Constantinople and the Palaiologan manner. The appeal of Cretan artists for Europeans was in their facility and skill for producing brilliantly finished decorative religious pictures. The majority of these icons for the export market were of the Virgin and Child and sometimes of Saint George and the Dragon; only occasionally the Saviour or a feast such as the Annunciation.

The three examples of Christ the Vine signed by Angelos, though they vary in quality and in condition, are all of monumental proportions and more or less iconographically identical composition. One of these, in the parish church of the village of Malles, Ierapetra on Crete, is well preserved and can serve as an example for comparison with No. 15 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Christ the Vine, Malles Church, Crete

|

|

||

No. 15. Detail |

Fig. 3. Detail |

No. 15. Detail |

Fig. 3. Detail |

Comparison between the figures of Peter and Paul in our icon and the Angelos icon in Malles shows us how close is the delicate painterly rhythm of folds and highlights and attention to detail, while faces are mobile, eyes intense and expressions lively. Each apostle seems to be alert and energetic, qualities derived from Palaiologan art of the fourteenth century and earlier as one sees in icons and illuminated manuscripts (Figs. 4, 5)

Fig. 4 Detail. Head of St Mark.12th century. Illuminated MS, Dionysiou Monastery, Athos |

Fig. 5. Detail. Evangelist Matthew, 14th century, Illuminated MS Dionysiou, Monastery, Athos |

Fig. 6. St George, detail, 16th century icon15 |

By the time of the sixteenth century faces had become conventionally interiorised and withdrawn and were painted with less individuality (Fig. 6). The European admiration for Cretan icons in the later period was based on the impressive skill with which they were crafted and also because they were reliably old-fashioned, an especially attractive quality for the conservative-minded, where religious imagery was concerned16. A commercial market for icons on the scale that developed between Candia and Venice was a new phenomenon in the history of art17. It is clear from the surviving contracts between dealers and artists in the late fifteenth century that part of the success of this venture depended on standardisation. Early fifteenth century icons, on the other hand, were stylistically, and maybe psychologically, closer to the spirituality of the monasteries and the art produced in Constantinople under the influence of Hesychasm as we see in Byzantine manuscript illuminations and in the fourteenth century mosaics and frescoes of the Pammakaristos and Chora Churches18. I think it is in that category that our icon belongs.

Apart from references in Angelos’ will we know little about his younger brother Ioannis except that he was also a painter and that he lived in the same house. As far as I know there is no icon attributed to him. Maria Vassilaki is convinced that ‘[Angelos] ran a large painter’s workshop in Candia. Important artists from the second half of the fifteenth century, such as Andreas Ritzos, in whose work we find the stylistic mannerisms of our artist in more developed form, must have learned their craft there’19. Other celebrated painters thought to be associated with Angelos’ workshop are Andreas Pavias and Nikolaos Tzafouris. These painters represent the flowering of the generation of the Cretan School after Angelos in the second half of the 15th century and compared with whom our painter’s work is stylistically closer to the late Palaiologan manner. There is no evidence of ‘more developed form’ and we do not see the highly polished performance of Pavias or Tzafouris. The iconography of course is pure Angelos.

Fig. 7. Back of the panel with 1914 Christies registration number

Footnotes:-